Click here for Home

"FORTY YEARS OF RETINAL PHOTOGRAPHY"

by Genghis

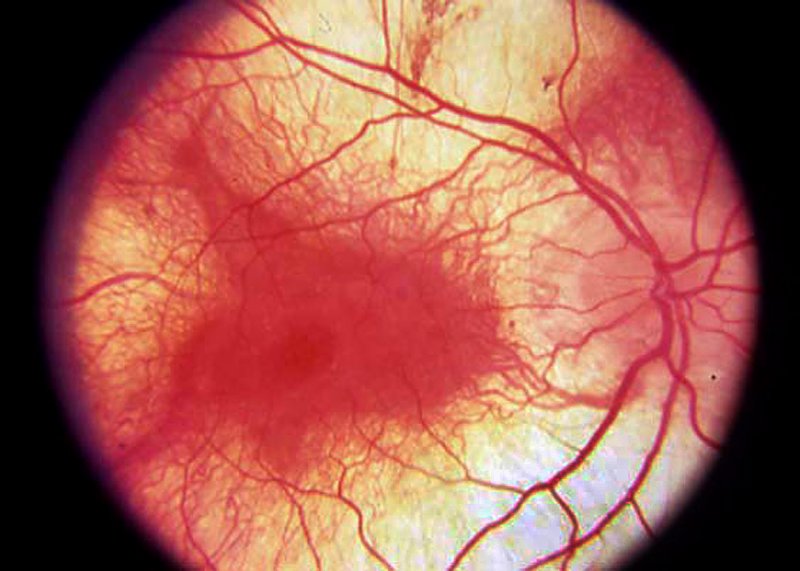

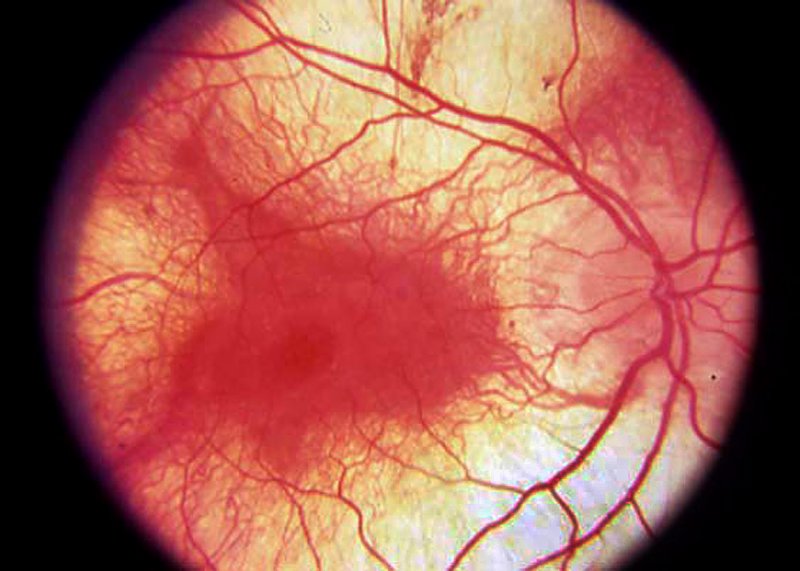

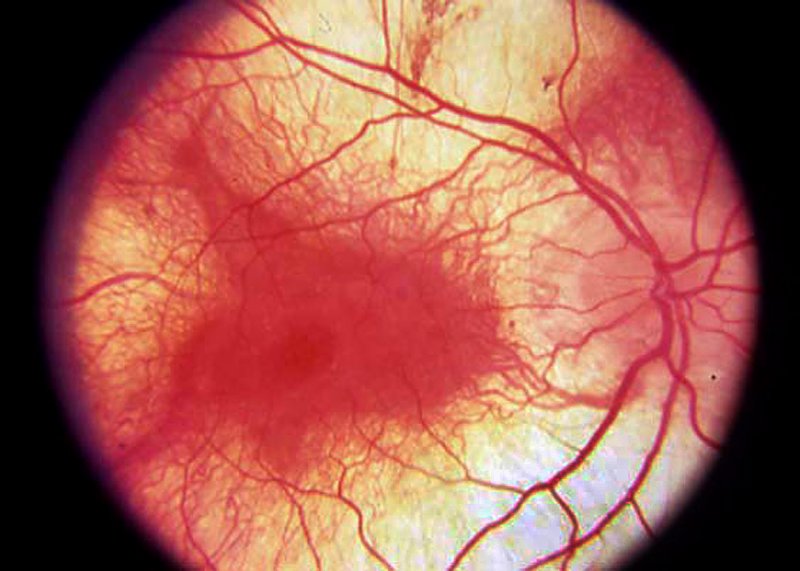

Photo by Genghis

An eye with choroidermia.

This memoir is being written in 2011.

In a few days, I'll be headed to Orlando, Florida to give my lecture, "Problem-Solving in Fundus Photography & Fluorescein Angiography" for the Joint Commission on Allied Health Personnel in Ophthalmology (JCAHPO), a group that is ancillary to the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO). When the AAO holds its annual meetings at different cities every year, ancillary groups like JCAHPO present their courses for its members. Another ancillary group is the Ophthalmic Photographers' Society (OPS) which my brother Don Wong, co-founded in 1969 along other illustrious medical photographers of the day.

Since Don's untimely passing a few years ago, I've opened my lectures with a dedication to my brother with good reason: Don was the guiding professional, as well as intensely personal force in my life with regard to photography.

I'm not abashed to admit that I suffered from a serious condition early in life, known as "Big Brother Hero Worship Syndrome." Everything my "big brother" was and did when I was a child, I wanted to be and do--only better. This last point is most germaine to our complex relationship over the years, that was infused with intense and conflicting elements of love, respect, and yes---sibling rivalry. It was sibling rivalry that decided the course of my teaching activities in ophthalmology, and undermined to some extent, my relationship with Don. I am convinced that sibling rivalry is one of the most compelling human emotions, sparking both great achievement at times, and personal destruction in some instances. It is a true compulsion to follow the dictates of sibling rivlary, bringing to mind the mantra of the Borg: Resistance is futile.

More on this later.

Because of Don's all-pervasive influence in my life, I've loved photography since my preadolescent years. There was a rebellious facet to all of this, as I will explain. You see, my parents' fondest wish for my brother was for him to become a doctor. With this in mind, they sent Don to Columbia University for his undergraduate work and premed studies. My parents were devastated, when Don marched into our Chinese laundry to proudly announce, "I've changed my mind about becoming a doctor. I want to be a photographer instead." My parents never forgave this act of rebellion. No matter. Don went on to become a freelance photographer. The way that I, a young and impressionable boy, viewed this ultimate act of rejection of parental control, cannot be underestimated: I was in total awe of Don and his decision. A photographer? How cool is that, I thought and more importantly, felt in my young bones. Who could a young kid admire more, a staid doctor, or a cool photographer? The answer was clear, not even close, man.

This is an introspective article, meant to describe my 40 years historically in retinal photography, as well as to elucidate my complex relationship with Don, whom I loved and respected very much. Sad to say, Don and I were quasi-estranged toward the end of his life, and I do miss him. Truth to tell, there are quiet times of solitude, when I wish I could still talk to Don, to repair the rent in our relationship. I believe that this type of familial adversity, and post-mortem regret, is commonplace with people. I am not alone in this. I feel that I owe Don so much, without the opportunity to properly thank him, deprived by the whimsical circumstances of life and then death. Death is the final arbiter of opportunity. I am stunted with frustration, at the impossibility of reconciliation.

Don taught me the rudiments of photography starting when I was about 12 years. old. He gave me an old Alpa SLR, which he trained me to use. I'd lug this thing around and practice my street photography, although I didn't call it "street photography" back then. Street photography is still one of my great passions.

By the time I reached 15, I graduated to a Nikon F and a Gossen Luna Pro hand-held exposure meter. I bought this Nikon F in 1962 at Willoughby's Camera Store at 31st Street and Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. Willoughby's is still there, and believe it or not, I still have this Nikon F and it is in perfect and functional condition!

By this time, I had a darkroom at home, equipped with a Durst enlarger, with which I specialized in black and white printing. Dektol, hypo and Kodabromide paper were the tools of the day. My expertise in photography, with Don as my tutor, was the preparation for my entry into photography professionally, although this thought was too amorphous when I attended Queens College. Some college-aged kids only have a vague idea of what they'll end up doing for a living, and I was one of these. When the opportunity arose to become a professional photographer, I jumped at it faster than a starving man mugging an opportune and helpless pizza with mushrooms and pepperoni.

Here was the deal: Early in his career, Don worked as the staff medical photographer at the Pack Medical Foundation, a medical group of head and neck cancer specialists. Don heard that Arnie, the photographer who held this position at Pack, was leaving his job. This was in 1969.

Don got me hired in his place. The surgeons at Pack performed complex cancer surgeries, but also performed more mundane procedures such as breast (as they called it in those days) "augmentation" and breast reductions. I must admit that the most gratifying part of my job at Pack, was the pre and post photography of women who underwent breast procedures. I'm sure you understand why.

The Pack Medical Foundation was located on a serenely elegant tree-lined street in the East 30s in Manhattan, near Lexington Avenue, where I had my own studio and darkroom on the ground floor. An ironic fact is that Arnie's fiancee Carol Shander, who also worked at Pack as a lab tech , ended up as our secretary in my current practice where I'm now the practice manager.

Unfortunately for me, the sometimes raucous ride at Pack ended with the bankruptcy of the foundation a year and a half after I started there. This led to unemployment, and a scrambling for a salary, any salary to support my young family, which consisted of my ex-wife Nancie and our infant son, Mike.

To this pragmatic end, I became a motorcycle messenger with the Quick Trip Messenger Service, using my beloved Harley-Davidson to put food on the family table and maintain the roof over our East Village apartment on East 3rd Street. I made numerous trips on my bike for the company out of state, including forays to Philadelphia and parts of Jersey. One of my regular runs was to carry computer tapes to IBM in upstate New York. The majority of my jobs took place within the confines of Manhattan, for customers such as ABC, CBS and NBC. During my many trips in the Big Apple, there were opportunities to seek another photography job. One of these interviews took place at Edstan Studios.

Edstan Studios was a commercial lab that specialized in both commercial work, as well as salon black and white printing for artistic pros, who were either too lazy or inept to make their own prints. This became my job. My experience at Edstan Studios mirrored Don's experience at Modern Age, where he worked sporadically to earn a living when he was a struggling freelance photographer. Modern Age was a similar pro lab.

Don has stated that he learned more at Modern Age about efficient print processing, than at any other professional venue. Looks like I was following the Don Wong Template for succeeding in professional photography.

My stint at Edstan was similar. It was at Edstan where I learned to make twenty prints at a time in a tray of developer, greatly enhancing the volume of my production. In addition to doing commercial work at Edstan for clients like TV Guide, ABC and NBC, I made salon prints for professionals who either didn't have the time to do this themselves, or were too ignorant about darkroom technique to make good prints. The beauty of many of their prints hanging in art galleries, may have been attributable equally, to their aesthetic sense, and my darkroom skills.

To them, "dodge" and "burn" might've connoted their choice of automobile, and what that car did with gasoline. My time at Edstan lasted until 1971, when I finally broke into ophthalmology.

In 1971, Don was once again instrumental in inserting me into a job. This was my first job in ophthalmology, when I became the ophthalmic photographer for the department of ophthalmology, at the Beth Israel Medical Center in Mahanattan. Don was acquainted with the department chief who he knew from his time at Mt Sinai Medical Center. Keep in mind that I had at this time, no work experience in retinal photography with the exception of one rushed lesson from Don on his Zeiss fundus camera. Don at this time had run ophthalmic photography departments at Mt. Sinai Medical Center and Flower & Fifth Avenue Hospital. On the day he found the five minutes to give me what might be charitably called a "barebones" lesson, Don had fifteen patients in his waiting room, impatiently awating their turns for fluorescein angiography.

I had never performed a fluorescein angiogram in my life, and I entered the job at Beth Israel with the chief's understanding that I was proficient at angiography, from my brother's glowing recommendation!

After I did my first angiogram at Beth Israel, which was wildly successful, I showed the results to Don. I was so proud. It was perfect, with every frame artifact-free. Don quizzed me on how I performed the angiogram . I proudly said that I looked around the camera and lined up the camera's light on the patient's eye, and shot the entire sequence that way--by looking at the eye around the camera. Don couldn't believe it. He said, "Scott, you're supposed to be looking through the eyepiece while you're shooting the study!" Live and learn.

Beth Israel's opthalmology department was in its developmental stages in 1971, an impression of mine that was confirmed when the department chief led me to my photography room: It was a converted men's room. This is not an exaggeration. It still had the diamond-patterned tile floor typical of men's rooms. The plumbing fixtures from the urinals that had been removed , were left protruding from the walls, silent witnesses to the fluidinous excesses of years past. A better imagination than mine might've smelled the sweet fragrance of urinal cakes.

The toilets and stall walls had been removed, but you could still tell where the toilet stalls once stood loud and proud. The holes in the ground where the toilets once drained, were still extant, unfilled and with no purpose. Couldn't they at least have put some fern planters there?

Along the wall where the sinks were, was a large stainless steel darkroom sink. Can you imagine an anxiety filled patient who was facing the specter of undergoing retinal angiography for the first time, entering this dark and dank dungeon for his or her test? Reassurance wasn't this environment's most important product.

At the time I worked at Beth Israel, I began to become involved with the Ophthalmic Photographers' Society (OPS), which Don saw as "his baby" since he was a society co-founder. The OPS consumed a large percentage of Don's life, and Don was happy that I was becoming enmeshed with the OPS. Don saw me as his protoge', and wanted to badly guide my professional life the right way. The right way meant being as betrothed to the OPS as he was. Sibling rivalry was to divert The Course As Plotted By Don, but not yet. By 1973, I had become as proficient at retinal photography and fluorescein angiography, as Don advertised me to be when he got me the Beth Israel job. Don's great passion back then, was to coordinate hands-on fundus photography workshops, and I participated as in an instructor in his local courses. These were sporadic meetings of the New York Chapter of the OPS.

An opportunity presented itself for job advancement, when I learned that the Director of The Retina Service at the Edward S. Harkness Eye Institute of the Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center, was looking for a retinal photographer for his private practice. The doctor was Dr. Harold F. Spalter, an renown authority on retinal detachment surgery, diabetic retinopathy and central serous retinopathy.

It was an attractive opportunity, because the duties involved becoming his assistant in the practice. This was a chance to broaden my knowledge base in ophthalmology, since Dr. Spalter intended to teach his assistant about retinal pathology, as he would an ophthalmology resident. I interviewed with Dr. Spalter and got the job, a position I would hold for 18 years.

I enjoyed working at Columbia-Presbyterian very much. Columbia-Presbyterian was large medical center, where numerous specialty buildings were separate satellites to the main hospital, revolving around the main hospital like planets around the sun. The Eye Institute was separated from the main hospital, by a large garden, which engendered a campus-like feel to it. Columbia-Presbyterian had a comprehensive tunnel system, connecting the satellite specialty buildings to the main hospital. like underground tributaries flowing from a primary body of water. I often took a shortcut from the main hospital through the tunnel to the Eye Institute, exiting at the eye clinic on the basement level, feeling like James Bond in that covert way, evading onlookers in the garden above ground.

Could "Spy Versus Spy" from Mad magazine be far behind?

The Harkness Eye Institute itself, was a large eight floor art deco buiding, consisting of two halves. One half was the clincal part where doctors' offices were, and the other half was the research wing, with the eye clinic in the basement, and research labs above. Our office, where we saw patients (and I performed angiography) was on the second floor of the clinical side. In addition to this though, I had my own lab on the research side, which consisted of an office and a darkroom. We qualified for a lab because we had grants to study diabetic retinopathy and central serous retinopathy.

The doctors' offices on he clinical side were laid out like residental apartments, which I understand they were at one time. Our office consisted of a reception area, my room and then Dr. Spalter's room. Both of our rooms had windows facing 165th Street, with adjustable black out shades. Next to our office was Jack Coleman's office. Dr. D. Jackson Coleman is the noted ultrasound authority.

I learned a great deal regarding pathology while with Dr. Spalter. He was a great teacher, and true to his word, he taught me like a resident. My duties in the practice expanded as my base of knowledge grew. After fluorescein injections, after early and late phases of angiograms, Dr. Spalter and I collectively examined these patients using angioscopy. With an excitor filter on his American Optical indirect ophthalmoscope and a "teaching lens" attached, he and I were able to see the fluoresecin patterns develop in these eyes, that were later confirmed on the angiographic prints. I learned how to interpret angiograms this way. Besides photography, my expanded knowledge allowed me to "triage" our patients as they presented, and I made decisions before each patient saw Dr. Spalter, regarding whose pupils to dilate, depending on patient history and symptoms.

This facilitated patient flow, as Dr. Spalter now had someone---me---who was able to perceive patients' diseases and exam needs as he did, and acted accordingly.

This type of broadbased knowledge is something that a pure retinal photographer doesn't have access to, because of the narrowly focused way that retinal photographers interact with patients.

For a year while at the Eye Institute, I had the opportunity to be an instructor in the Ophthalmology Residents' Basic Science Course at Columbia's College of Physicians & Surgeons. This consisted of hands-on instruction of the third year residents, and a lecture on technique. It was well received and appreciated by the residents, but was halted by the departmengt chief, Dr. Charles Campbell, when he discovered that I didn't have the academic credentials to warrant this teaching position. At this time, I became more involved with the OPS when I attended my first American Academy of Ophthalmology & Otolaryngology (this was before the eye and ear groups went their separate ways) in 1974. I believe this was in Dallas. At this meeting, I taught in my brother's hands-on OPS fundus photography workshops. It was also in this era at Columbia-Presbyterian, when I gave my first lecture.

I gave my first lecture in 1976, and it was a lecture to three hundred ophthalmologists. To say that I was nervous, given the demographic nature of my audience, would be a gross understatement. It's like a rookie NFL quarterback, getting his first start under center. The occasion was the annual meeting of Columbia-Presbyterian's Ophthalmology Courses, and the venue was the staid and tradition-bound Alumni Auditorium at the College of Physicians & Surgeons of Columbia University. I seem to remember that the names of alumni were emblazoned on plaques attached to each seat back.

There was an ophthalmic photographer in the audience, and this was Tom Van Cader. My first taste of lecturing hooked me but good. My lecture was titled, "Techniques of Fundus Photography," sort of generic, but it was successful. To Dr, Spalter's chagrin, I actually asked him for a raise (as a joke) during my lecture, which drew howls from the normally reserved ophthalmologists in the audience. My lecturing career continued in 1978 when I gave a talk at a meeting at the Cullen Eye Institute at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, coordinated by Johnny Justice Jr. At this time, I was OPS compliant, but this was soon to change. This was perhaps the turning point where my schism with my bother Don, was beginning to show cracks on the ground. Tsunami to come?

For some reason in the late 1970s, I became extremely disillusioned with the Ophthalmic Photographers' Society's failure to provide a journal. I felt that as professionals in the field, we OPS members deserved more than a mere newsletter, which I perceived as a gossip organ. I became so passionate about the issue, that I threatened to create the "Retinal Angiographers' Association." The "RAA" would publish a journal for retinal photographers, I vowed, but this would be its sole function: To publish a journal. It wouldn't sponsor meetings. Nevertheless, some in the OPS felt threatened.

I guarantee you, that you will never read about this in the history archives of the OPS, but older members will remember this blip of an historic episode. It was I believe, significant, because it did provide the impetus for the OPS' creation of The Journal of Ophthalmic Photography, as a direct result of the unrest and anxiety my RAA threat presented at that time. In fact, Don was the direct beneficiary of this movement toward an OPS journal, as he was charged with being it's first editor, after a journal was approved by the OPS' movers and shakers.

The reaction to my RAA actions, were seismic and volatile within the OPS. I received a letter from Johnny Justice Jr. condemning my "behavior," for...."using the OPS mailing lists for your own devious purposes!" I still have this letter somewhere.

Johnny and I are good friends now, but at that juncture, he was livid with me. He wasn't alone. My brother Don felt embarassed and betrayed, that his own brother would work in a counteractive way to his baby, the OPS. It was only after the dust settled, and the OPS finally agreed to publish a periodical journal, that I relinquished my plans for the Retinal Angiographers' Association. All was forgotten, and OPS members came out ahead, with an ophthalmic photography journal forged in the fire of threats and coercion. Not that you'll read any of this specific history in the OPS annals. The only source where you'll read the lurid details, is right here.

I did by the way, have an article in the inaugural issue of the journal, as well as additional articles in subsequent issues.

At this point, my relationship with the OPS was calmed down, but tenuous. The final schism with the OPS and by extension my bother Don, took place starting in 1982. Doris Gaston of the Joint Commission on Allied Health Personnel in Ophthalmology (JCAHPO) approached me in 1981 about possibly taking over their retinal photography course. Doris invited me to scout the course as it was given in 1981. This "hands-on" course consisted of two photographers sitting at a dais where a fundus camera was parked, answering questions from students about technique. The two photographers were Bill Ludwick and Tom Van Cader. At no time during the course, were any students allowed to touch or function with the camera. After seeing this sad display, I agreed to displace Bill and Tom the following year. This was my chance to compete with my brother in the arena that he loved: Coordinating and teaching hands-on retinal photography workshops.

Sibling rivalry lives.

Here's where it got tricky with the OPS the next year. In 1982, I made it my business to obtain the use of manufacturers' retinal cameras for my course ahead of the OPS.

The OPS would've had to use the same equipment for their fundus photography workshops. You see, each camera manufacturer only transported enough equipment to the annual meeting, for use at one venue at a time. My coopting the cameras before the OPS had two effects. Number one, they had to wait until we were done at JCAHPO, before they could use the same equipment. Secondly, my JCAHPO hands-on workshops, diluted the number of students that atended the OPS workshops. Previously, many of the students that attended the OPS workshops for JCAHPO accreditation, were JCAHPO students, who now obviously would be going to my JCAHPO workshops instead. The convenience of JCAHPO students attending the JCAHPO workshops in the JCAHPO hotel, was a huge factor in drawing students there, instead of the OPS workshops at a distant hotel.

My workshops drained the student pool for the OPS workshops, leaving only OPS members to attend their courses.

The OPS wasn't happy about the diminished numbers at their workshops.

The eruption within the OPS over my workshops, was predictable and palpable, even across the distance between our meeting hotels. I ran these JCAHPO workshops from 1982 to 1986, and each year I made it my business to contract the cameras for my courses, ahead of the OPS. It also meant that the OPS had to schedule their courses later in the week, after I was done with the equipment--an inconvenience they didn't suffer when they were the only game in town.

As a salve, I agreed to personally transport the cameras to the OPS site. I rented a truck to do this, which JCAHPO reimbursed me for. I did this with the help of the instructors I drafted for my workshops. Try to picture this in your mind: Future presidents of the OPS, such as Jamie Nicholl and Larry Merin, helping me to lug fundus cameras into a Hertz cargo van, all of us sweating and huffing and puffing, in an attempt to assuage the anxiety of the Ophthalmic Photographers' Society!

It was quite an illustrious group of instructors I enlisted for the first set of workshops in 1982. These took place at the Hyatt Regency Hotel in San Francisco, and it repeated once during the day. My instructors were Kenneth E. Fong, Frank G. Flanagin, Philip K. Chin, Dorothy A. Fong, Doris Cubillas, Nancy K. Hathaway, Dennis J. Makes, Deborah Ross, Lawrence M. Merin, Michael Sobel, Jamie Nicholl, Sadao Kanagami and Dr. Harold F. Spalter. Each three hour workshop was preceded by my slide lecture on technique. My JCAHPO workshops included a teaching technique never used before, which was my brainchild. This was simulating fluorescein angiographic studies, complete with false injection, and the shooting of the early phase with motorized bodies.

This, from the course description from the 1982 program:

"....Special emphasis will be placed on the simulation of angiography. Each participant will have the opportunity to repeatedly 'perform' angiography in a simulation of a clinical setting, with particular attention to the timing of the angiographic squence after 'injection.'......"

Because the performance of angiography had never been simulated in workshops before, camera vendors were puzzled about why I insisted that their cameras come equipped with camera backs with motor drives. Hey, ya can't simulate angiographic timing without firing off those motorized cameras, man. Of course, in 2011, this simulated angiography, termed "mock angiography" since by the OPS, is familiar territory. However, in 1982, it wasn't at all SOP (standard operating procedure). SOP before my workshops, was to concentrate on single image achievement, neglecting the most dynamic and taxing element of a retinal photographers job: Proficiency at performing fluorescein angiography.

Students at my workshops were required to bring one twin pack of Polaroid film. This eliminated the problem of film procurement for me. Students were also requested to agree to have their non-dominant eye dilated (barring any medical contraindications) for practice purposes. Previously, other workshops depended on either a few scant volunteers to be dilated, or model eyes--not good enough. This way, we had an equal number of dilated eyes for the same number of students.

This year, I will have taught for JCAHPO for 30 years. I've given lectures on technique, as well on fluorescein interpretation. It was sibling rivalry that drove me to JCAHPO.

The divisive feelings that resulted from my intense competition with OPS in the '80s, kept me from feeling a comfort level with fully participating in the OPS. It's a chemistry thang.

Of course, the current OPS is unaware of me, and of my past competitive struggles with the society. A whole new generation of retinal photographers has come of age, since the 1980s.

Once I took refuge away from the OPS, it became difficult to identify with the OPS, even though I'm still a member in good standing. In the intervening years that directly followed my workshops in the '80s, my relationship with Don cooled and eventually fractured, exacerbated by familial problems that arose regarding our mother in the 1990s.

This year, as I get ready to fly to Orlando for the annual meeting, I've been engaged in retinal photography for 40 years. I work as the practice manager for a private practice in Greenwich Village, where I've worked for the past 20 years. In my expanded role, paperwork and surgical coordination have rivalled retinal photography in my schedule. My role with patients has grown, as well.

Over the years, my interaction and relationships with patients have grown more expansive, becoming more empathetic and personal in both directions, in ways that would not have been possible if my activities were to be restricted to fundus camera work. I have continued to lecture.

I've given courses every year for 30 consecutive years, that must be some kind of record. I have taught at least nine thousand photographers and techs techniques of retinal photography. From this, I get great satisfaction. Do I sometimes wish that I'd expended this time and energy in my bother's "baby," the OPS? Perhaps. I had a complex relationship with Don, with the urge to gain his approval counterbalanced by our sibling rivalry. I was extremely conscious of the tug in both directions.

The course of my teaching career was dictated by, and sustained by sibling rivalry. It is what it is. Later.

FINITO